DEWEY McMILLIN: ESCAPE TO TRONCONES

He came, he saw, he got away from it all and made a difference

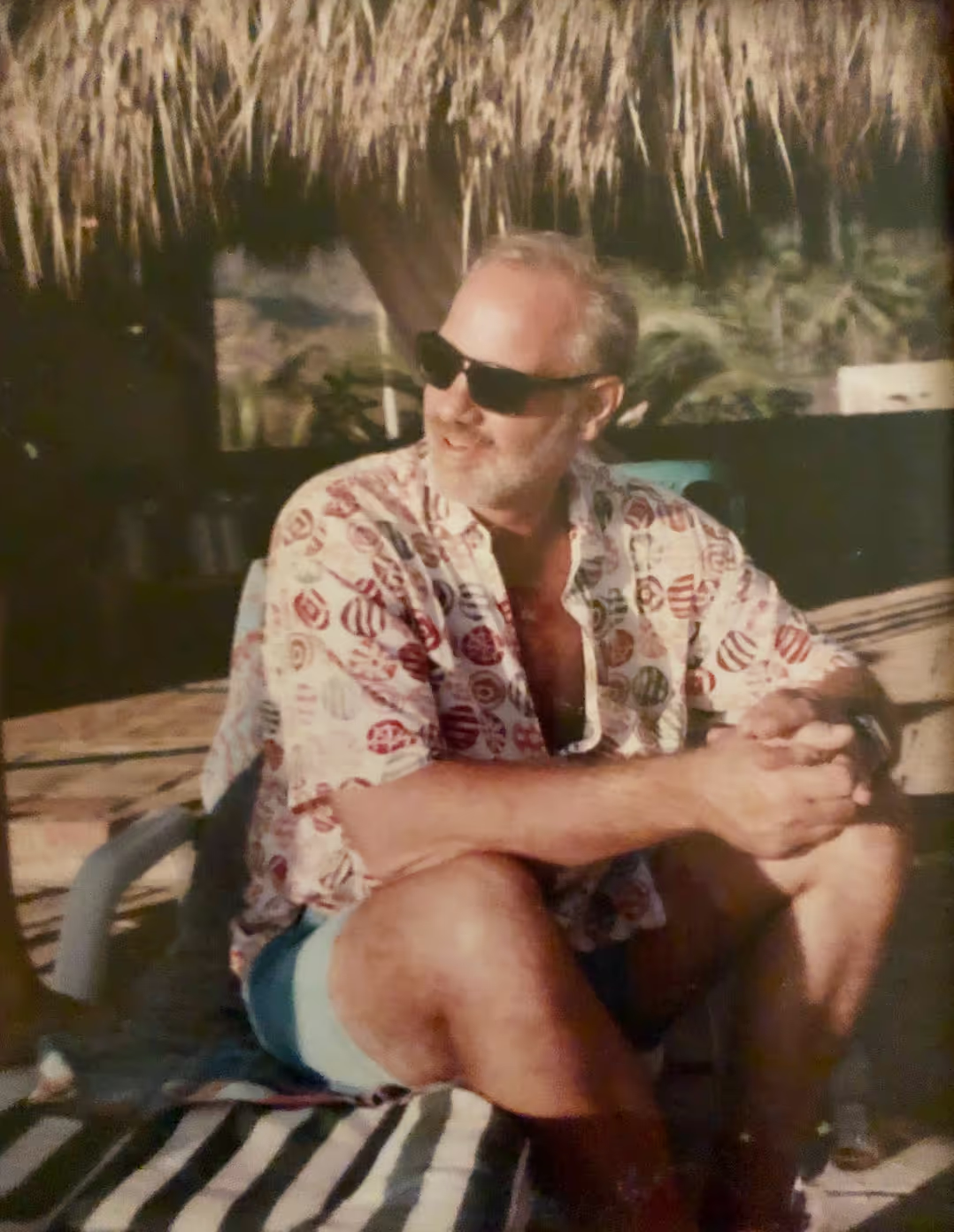

He’s smooth. Even his name is smooth. Dewey McMillin. Like a fine blended scotch or a big wave surfer. Dewey McMillin. It’s a name that holds reverence. Especially here in Troncones. It’s widely acknowledged Dewey is responsible for the development of 21st-century Troncones, helping the community attract homeowners from around the world, transforming an isolated village into a legendary destination. In 2019, at Troncones’ annual February Expo Feria (carnival), the community celebrated Dewey’s commitment and tireless work in bringing in the essential infrastructure—for roads, electricity, water—that wasn’t here before. His selling of beachfront lots, in partnership with the community, also brought in jobs—the construction, maintenance and service work needed to sustain a growing resort, and that assure on-going opportunities for local families. A profile of Dewey in The Wall Street Journal, from January 6, 2000, opens with “Former Alaska fisherman Dewey McMillin has done something unique in the world of Mexican beachfront development. He’s made everyone happy.” It also quotes Dewey describing how to create success in business here, saying, “The trick is not to leave your brain at the border.” That’s his kind of smooth.

%2013.19.36.avif)

THE BEGINNING

LOT: Is there any truth to you being “an Alaska fisherman”?

DM: Sure is; I was a commercial fisherman in Alaska for 17 years. I started in ‘72 or ’73, out of Seattle, and I did that until late ’89.

LOT: How did you end up doing that work?

DM: I was working in a bar in West Seattle, the Alki Tavern. It was a Thursday happy hour. One of the guys drinking at the bar owned a fishing boat and liked the way I was working–I was serving probably about 150 people–so he hired me to go to Alaska and work on his boat. It was seasonal work. I’d go up there and come back to Seattle. We’d go after salmon or crab or halibut, depending on the time of year. That first time was salmon, summertime in Prince William Sound. Total paradise.

LOT: From Seattle and Alaska, how did you happen to come across Troncones?

DM: I had friends who I fished with from West Seattle who had been coming down to Zihuatanejo since the ‘70s. Because fishing was seasonal work, a bunch of them were coming down here one winter, so I came with them, to Zihua. That was probably November or December ’83. We stayed on [Playa] La Ropa. Party town. Gitano’s Restaurant. Live music. Swimming every day. Food was cheap. Rent was cheap. Beers were 15 cents each. It was a good time.

A couple years later, there were six of us living in a house La Ropa. It was right before Easter and the landlord had the house rented to someone else. They kicked us out. We came out to look at this house [Casa de la Tortuga]. It was two-thirds finished. No electricity, no water; there was basically no road either. The owner wanted $15,000. When we got in touch with him he said was going to rent it, but when we got out here, he said he’d only sell it, so, he sold it to me and two of my friends for $15,000. This house and Casa Blanca were the only houses on the beach. That was 1985. We bought it within four or five days, and we moved in. We called it, “camping in a mansion”.

LOT: Were all these building set up? Did they have roofs?

DM: They were like concrete cubes set on dirt. They had roofs, but not all of them had doors. There were no plants. There was no patio. No water was the big thing. We had a cistern and had to figure out about getting pipas (water trucks), where to get them. We had to buy a generator to pump water. No electric. We got a propane-powered refrigerator. It was an experience.

LOT: Who was the guy who built the house? Who did he build it for?

DM: Pedro Blankenhorn; it was for him and his family. He got into trouble with the village. They basically didn't like him.

LOT: What did he do?

DM: He acted like he was better than them. Happens a lot. Not nice. After we bought the house, he got out of town.

LOT: Did people here help you? With pipas, generators and those sorts of things.

DM: Not right away. We knew a lot of people in Zihua who helped us out a lot as far as finding pipas, generators, workers to come put doors in, screens up. Like I said, my friends had been in Zihua since ’73. By the time we got here, that’s where we were connected. We used who we knew.

LOT: You mentioned Casa Blanca was the only other house on the beach. Who owned Casa Blanca? Did he help you?

DM: That was Paulino Landers. He was a Spanish guy, with a couple of daughters. He had property up in Lagunillas, too, which I think the family still owns. He didn’t help us.

LOT: What did the people in Troncones do when they saw you coming

DM: At first, they hid behind the coconut trees. Why? Because we were the foreign devils. There were two cars in Troncones when we moved in here. One was ours and one was Ventura’s [now the owner of Materiales Troncones]. We started giving people rides to the main road and to Zihua, and back. One of my partners, Ryan, had a Mexico City girlfriend who didn’t trust the locals and told us we couldn’t talk to them. She got in the way. I bought Ryan out. It took four or five years until people were really comfortable with us.

By then, things had changed a little in the village. For instance, I had to buy the house again. The first time, I bought it from Pedro Blankenhorn in a fideicomiso (real estate trust, administered by a bank), in ‘85. Then the government gave all this land to the ejido, in like ‘87 or ‘88. [An ejido is a local collective responsible for governance of land and water, the essential assets of rural communities.] The ejido here kicked Paulino Landers out of his house. The same happened to a Swiss guy living up on Manzanillo Bay. There was an assembly in the schoolhouse. Both those guys went ahead of me. They both said they’d already paid, that they had their paperwork. People in the ejido were voting with machetes, and they told those two, “You got two days to get out”.

LOT: Voting with machetes?

DM: Slap the desk once for No and twice for Yes. Pretty intimidating. So, when I got up, I said, “Let's make a deal. How much do you want?” I paid $12,000, I think, but I made a deal that we pave the main road into Troncones with that money.

LOT: The road from the main road was unpaved, even in the late ‘80s?

DM: Yeah, it was horrible. There was no equipment to fill in holes or grade spots that got washed away, anything like that. From here [downtown Troncones] to the main road, it was a good 30 to 45 minutes. And another 50 minutes to get to Zihua. A one-way trip there was almost two hours.

LOT: After the road was paved, were you embraced then?

DM: Oh, not completely. But then I moved here full-time. January 1, 1990. And in about ‘91, ‘92, I started selling land. Beachfront lots.

LOT: How did you get to doing that?

DM: After I was here full-time, I went to work in Ixtapa selling timeshares, but I started bringing people out here to lunch at my house. They’d ask, “I’d like to buy a lot. How much for a lot?” In those days, $3000 could buy you a beachfront lot on ejido land. A quarter-acre, 20 meters by 50 meters, 1000 square meters. After a couple sales, the village started getting some money. I put electricity in; I helped put water in; I put a road in along the beach.

LOT: From your timeshare sales and beachfront sales? Out of your own pocket?

DM: Sometimes it was out of my own pocket. Sometimes I could get the ejido to help me. Sometimes not, depending on who was in charge.

LOT: When you moved down here full-time in 1990, did you sell everything you had in the States? How old were you?

DM: I was 40. I owned a house and sold it. I got about $60,000 out of that and bought a 1967 Ford school bus. I loaded that bus up with everything I owned and drove that down here. My neighbors in Seattle thought I was absolutely crazy, which I was.

LOT: What made you think this place had opportunity?

DM: I was raised on Alki Beach in Seattle. When we moved there in 1955, it was all little post and pillar homes, right on the beach. It was Seattle's getaway. You drive along that beach now and it’s like Miami Beach. Condos, wall to wall. It’s just what happens with beaches.

You can take an aerial of this beach and an aerial of the beach I was raised on, and they’re almost identical. I knew what was going to happen here. Zihua and Ixtapa had plenty of tourists, and I knew that if they came out here and saw this beautiful, pristine beach, they’d buy. I mean, what’s not to love?

At that point an ATV drove up the beach. An unusual sight in Troncones. Motorized vehicles are not permitted on the beach and are rarely, if ever, seen.

THEN & NOW

LOT: You mentioned the government gave the property to the ejido. How did that happen? Didn’t the ejido already have it?

DM: When federal government started building Ixtapa in ‘69 or ‘70, their plan was to to do a mega-resort, like Cancun, all the way to Troncones, all as one resort. They expropriated the land. Pedro Blankenhorn actually bought this lot directly from the government. When government abandoned that resort plan, they gave it back to the ejido, or, more accurately, after they had brought in our ejido, our villagers, to work here, to clear land, make roads, construct hotels, then they, as governments do, gave up. Troncones sat, somewhat forgotten, for about seven or eight years before our ejido applied for the land and got it.

LOT: How did you go about selling off the ejido lots and helping people build out?

DM: Word of mouth, mostly. I started bringing people out in my car. Then, I started having friends bring people with me. Then, I started renting buses and became a sort of tour guide on the bus. I’d give a little speech on the way out, saying things like, “By the way, if you’re interested, there are beachfront lots for $5000 or $10,000, however much as they were at that time.”

LOT: When did you become involved in El Burro Borracho?

DM: That would’ve been ’93 or ‘94. It got to be too much to have that many people come here, to this house.

LOT: What was El Burro Borracho before you bought it? [Now, it’s El Chiringuito de Fran]

DM: It’d been a government project. The property had five bungalows on it, three of them were duplexes, and a restaurant. The restaurant operated for one year and went kaput. It was built out of rock, so the bones were good. The doors were gone. The roof was gone. It was in bad shape. A woman I knew in Zihuatanejo, Anita LaPointe, who had just inherited $250,000. I needed money to rehab it, so I went in and got Anita, picked up a cheap bottle of gin, and sat down with her and convinced her to go in as partners with me. When we were about through with the bottle, Anita asked, “What are we going to name it?” About that time, six burros walked out of one of the bungalows—there was no doors on those either—and I said, “Burro Borracho”.

LOT: The Burro has a lot of lore. How would you describe it? What was it like?

DM: It was a clubhouse. There were about six of us there, that’s it. We were there every day–drinking, smoking dope, watching sunsets, giving tourists shit. Living a beach-bum life. I started having music. It was a ten-year party. It got kinda famous.

LOT: I’ve heard Keith Richard came to visit and stayed.

DM: Yeah, he brought his wife and his two kids. Carolyn, the gal I came down with in ’90, was into exotic cats, which she kept here at this house. Ocelots and a couple others. Somehow, she connected with Keith and his wife in Zihua and brought them and the kids out here to look at the cats.

One week it’d been really slow and I needed to fill the place to make payroll. Supposedly Bill Gates’ yacht was in the harbor in Zihua. That was the big chisme (gossip, rumor) going round. I told three people, “Don’t tell anyone, but Bill Gates is coming tonight. It’s supposed to be a secret, but you should come down.” That night the restaurant was full. Everyone came to see Bill Gates. I told those three because I knew they’d spill their guts. There was some tourist who had a baseball cap on, who was kinda hunched over, I told everyone that was Bill. Half of them believed it. I used to pull shit like that to fill the restaurant up.

LOT: How did you promote Troncones, besides saying Bill Gates is coming?

DM: Like I said, I started bringing tourists here, six at a time, and taking them back. Not easy. I kept it cheap, too, like, $15 for a ride out and back, including lunch. Beers here were 11 cents then so I could do that. Anyway, those tourists would go back, good and drunk, and they’d tell other tourists, “You know, you got to go out and try this. We found a secret spot, a special spot.” They would tell everyone around the pool and that got other people interested. There were three restaurants I would go into in Zihua and people would be waiting there to go on my tour. I’d pick them up and bring them here. Eventually, I started to work the hotels in Ixtapa. That’s when I started getting busses. I think my record was three buses in one day. All coming to the Burro, all just by word of mouth.

LOT: What's kept you here all this time?

DM: In ‘88, I sank for the third time, out of Seattle, off the coast. Fishing is a dangerous business. I’ve sank on three boats. This third time, I was in a survival suit in a life raft for five-and-a-half hours, winds blowing 70, in 30-foot seas. I decided I didn’t want to fish anymore. I had this house in Seattle and I sold it. I put everything into the bus to move down here and made a commitment to stay five years.

I knew if I didn't make a commitment like that I’d go back. It’s hard cutting your ties, you know, bank accounts, utilities, all that stuff. I said to Carolyn, “We’re going, and we’re going for five years, hell or high water. We’re going to have some rough patches here, moving down to a house without electricity, without water.” She was okay with it. She wanted to change, too. She was a dog catcher, working for the pound in Seattle. We both wanted drastic change and this was it. I came down here with a fishing mentality. I was roaring to go. I could work 14 or 15 hours a day. No problem. And I did and I loved it. It was great.

LOT: How long did you sell real estate for here? Are you still active?

DM: I think I sold my first lot in ‘93. A few years ago, I turned it all over to Winter Ramos [tronconesproperty.com]. I still have old clients who like working with me, but it’s nothing like the way I was working before. I’m semi-retired, I guess.

LOT: What are the biggest changes you've seen in Troncones.

DM: Condos. Before it was all private homes or small hotels.

LOT: Do you see condos being sustainable here?

DM: They’re everywhere around the world, but they’re an interesting thing here. A lot of the people who buy a condo end up buying a lot and building a house for themselves. Not years later; sometimes, it’s just six months later.

If you're only coming for a month, or two months a year, a condo is a good way to go. In condos, someone takes care of it for you. It’s just money—you pay the money and it’s taken care of. You or the condo can find people who will rent and hopefully pay for your fees. If that happens, your condo ends up not costing you anything. If you’ve got a house, it’s costing you year-round. You’re looking at a minimum of $30,000 a year for everything, taxes, staff, electricity, water. If the money and the passion are there, what do you think? It’s easy for me. I like having a house right on the beach with no one really that-close, next to me.

LOT: If the biggest changes has been condos, what are the biggest changes you see coming?

DM: I’m hoping the new zoning from La Union restricts the building. The Association for the Preservation of the Environment of Troncones (APCAT) and the ejido were very involved in outlining those new rules. We’ll have to see how those work.

There’s this new development south of Troncones, near Buenavista, called Riviera Troncones. That’s going to be the biggest change I see coming. It’s a huge project by a big Mexican development company. The lots are 500 square meters, an eighth of an acre, half the size of what’s been sold for years. I don’t even know how many lots there are, something like 120, off the beach, on the mountain side of the road. They’re planning a clubhouse on the beach.

It’s about $100,000 to $125,000 per lot. Building here now is about $250 per square foot. Do the math: 1200 square feet, you leave yourself some room for a garden, a patio, that’s $300,000. Those buyers are looking at $400,000, maybe, $500,000 to get all in. That’s the same price point as some of the condos.

LOT: How much land is left to buy?

DM: If you look north, towards Majahua and La Boca, you’ve got that whole beach. If you go south, you’ve got all of that, still. From the south bridge in Troncones to Majahua, there are 300 beachfront lots in five kilometers. A little over 200 are built on. There are almost 100 beachfront lots, let's say, more or less, at $500,000 each.

LOT: And on the other side of the street? Towards the mountain?

DM: There’s a lot of land, but if you're a foreigner, you come here and you want to live on the beach. On the mountain side on the road, those lots are typically $150,000, for a quarter acre. It’s still the same price to build whether you’re building across the street or on the beach. Me, I like living on the beach. It’s tough; it's just like owning a boat. You’re dealing with the elements all the time.

LOT: What do you like most about that decision you made when you were 40?

DM: Going back to Seattle and seeing my old friends, knowing I had a better life. They’re still doing the same things.

LOT: What makes Troncones so special for you?

DM: Friends, the people I know, the people I’ve met. We could go out every night to dinner with someone, if we let it get away. But we don’t. It’s a great community. We’ve got the surf, the sunset, the whales, the porpoises and all that. What’s real nice is knowing everybody and being able to talk to everyone. That’s pretty cool. I keep seeing across Europe, there are towns, tourist destinations, like Venice and Barcelona, that are starting to charge people to visit. Some other places are closing down entirely because of too many tourists. That’s not our problem here. You know what’s probably a good slogan for Troncones? “Go Where the People Aren’t”, something like that. The people who come here seem to appreciate the space we have and the connections we’ve got. That’s pretty cool, too.

Link:

Dewey in the Wall Street Journal: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB947115537333694471

%2017.27.38.avif)

.avif)