J. Santos Jaime Sánchez: Lessons Learned

Part One

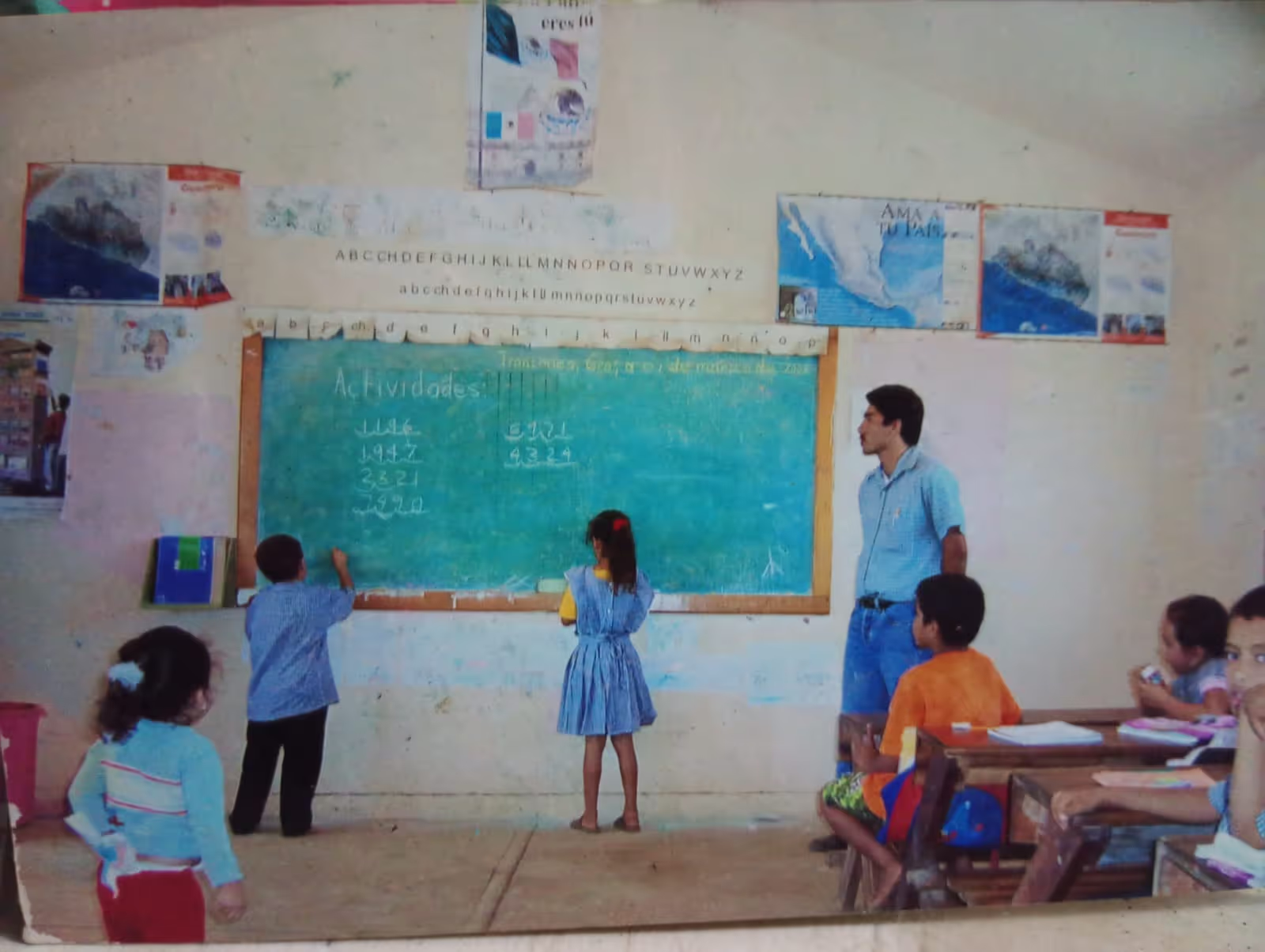

Good teachers are easy to learn from. They inspire you; they get you to think about the world differently; they make the learning fun; they set you off, curious to learn more. That’s Santos. When Aura wanted to take Spanish lessons, Santos arrived at our house carrying dominoes and a deck of cards. He doesn’t speak English, but he knows playing encourages connection, communication and conversation. He also knew that by talking over a game, he would discover what Aura needed to learn, where he needed to guide her. Santos is currently working in school administration in Coyuca de Benítez, four hours away, but he still lives in Troncones. He doesn’t want to leave.

When I sat down to talk to Santos for the first time, I was impressed by his calm. I also enjoyed he was using games to teach, because I’ve come to understand, after years of coaching high school baseball, that words don’t teach, but playing does. I’ve never beaten Santos in dominoes, but I’ve always gotten the best of him. His best comes out of him easily, smoothly, naturally, in what he has to say about life here, the history of Mexico, about how things work and don’t work. When I asked to interview him, I knew I was in for a ride. Most of my interviews go about forty minutes, sometimes fifty minutes to an hour. In answering my first question, Santos riffed away for twenty minutes. I didn’t stop him; it was too much fun. Two hours later, I came away with more than anyone would want to read in one sitting. Meet J. Santos Jaime Sánchez, educator and one of the bright lights of Troncones. Part One.

LOT: What did you discover when you arrived in Troncones?

Santos: From the moment I came off the main road, the first thing that caught my eye were the trees. They were immense and full. They created a spectacular canopy. And there was a small mountainous ridge that hugged the road as you went up the hill, trees here, trees there. I immediately knew I was in a special place. I came to Troncones because I had been invited by the municipal president of La Unión to a restaurant owned by Doña Madea that was on the beach. I was working in La Unión, at the Ignacio Manuel Altamirano School, as part of an educational program sponsored by the government. After we ate, I walked the beach and I knew I had to find a way to be transferred here, because I liked the feeling of being here.

There is a natural diversity in Troncones unlike the other places nearby, like La Unión, like Petacalco, like Zacatula. This is a place where there is nature you can feel, where you can enjoy the sea, the hills and the forest. That really caught my attention. I managed to get transferred, on November 11, 1998, and I’ve enjoyed it here ever since. I found myself within a community of wonderful people, people who gave me the opportunity to work with their children. I was still a student then, pursuing my bachelor’s degree in elementary education. When I met the mothers and fathers of the students, I saw and understood how much this is a community.

A community is not just any town. It’s a place where people are committed to one another. After I arrived here, people fed me in their houses. They knew I was a student, working as a teacher. They made sure I had a place to sleep, to rest. I felt like we were all working together to educate the children. As a tutor, I had the opportunity to visit all the homes, to meet each of the mothers and fathers who had children in elementary school. That helped me get to know the people.

One of the things I like about Troncones is all the different activities people do–the fundraisers [kermes], the cockfights; the volleyball, basketball and soccer tournaments. It is remarkable to me that the ejido of Troncones has donated the land and facilities to have these activities. And then, there’s the beach. I like how people gather to spend time with their families, not only from here, but from other places; how people come to enjoy the nature we have; how people come from all over to enjoy our peace and tranquility.

Today, the community is much bigger. In 1998, there were approximately 300 people. I remember that because I became involved in the political process, participating in elections through el Instituto Federal Electoral [the Federal Electoral Institute]. I was given a sheet with the names of all the people who could vote, and there were nearly 300. Today, I believe, we have exceeded 1000 people who live here, who can vote. If we count the students of the elementary school, the telesecundaria [middle school] and the preschool, we’re probably close to 1500, maybe a little more. In the last few years, many people have arrived from Querétaro, from San Miguel, from Morelia, from Lázaro, from Zihuatanejo, from Petatlán, from different places. These people come from the mountains to live here because, apart from its beauty, this town has another characteristic: there is a lot of work, work provided by foreigners, work based on the economic possibilities created by tourism.

Here in Troncones, much of the coastline has been sold by the ejidatarios [members of the ejido. The ejido is a cooperative that administers the use of the area’s natural resources. It consists of people from every aspect of village life]. Some of the ejidatarios still have land directly on the ocean, but most of them have sold their land to foreigners, to Americans, Canadians, to people from different countries around the world, to people from Mexico City. Those buyers come with the intention of having a place here and, often, to build businesses, too. I’ve observed the new people building bungalows and small apartments, and that they rent them. They rent spaces within their own properties, so, at the same time they, the foreigners, acquire a benefit, the people of the town also receive a benefit because they have work and, possibly, places to live. The foreign community also hires people who are not from Troncones. people from Pantla, from Lagunillas, from Buena Vista, from Zihuatanejo. They do that because the labor capacity of Troncones is just not enough; they have to bring more people in.

Some people of the foreign community do not rent their homes. Those people, too, hire Troncones citizens to help with the maintenance and upkeep they need. And that’s wonderful because it resolves the lives of the people they hire, it gives them work, a salary to feed their family. In some houses, local people stay to live on the property, so that they are living on the same land where they work, of course, the owners respecting their privacy, and that supports the owners with surveillance at night, giving security to their space. So, this place enjoys peace and the people enjoy having a means, through the foreign community, to acquire the money needed to bring bread to their homes, to their families.

Another nice thing about our foreign community is the different organizations they’ve created. Since I’ve been here, I have observed foreigners arriving with suitcases of pencils, pens, paints, notebooks, sports gear and sometimes even t-shirts and clothes. Those are given to the school and the school gives them to the children. But there is one thing that I want to comment on. I have observed as a teacher, that in spite of these generous organizations, like Las Hermanas, a group that gives scholarships to students to pay part of the transportation to go to study outside of Troncones, there’s still something missing. [Troncones has preschool, elementary and telesecundaria, but it does not have the high school level so, at that age, to continue their studies, Troncones students have to be transported to communities that have those schools, like La Unión, like Pantla, Zihuatanejo, Petatlán or Lázaro Cárdenas] When the students who earn those scholarships finish the telesecundaria, Las Hermanas pays part of their transportation expenses. This has helped a lot of students to decide to continue with their studies, even if they still have to find a way to cover the cost of their food and their books.

Part of the community is content to settle for employment with the foreigners. Once they are employed by the foreigners, they feel that their life is already resolved, that they have enough for everything and, effectively, their aspirations remain there. They are already employed, so they no longer continue with their studies. They stay here working with the foreigners which is good for them because, like I said, it resolves their life for them. But I’m starting to observe there are Troncones students with aspirations for professional growth, which is also good because that will help Troncones grow vertically, professionally. We need doctors, veterinarians, engineers, accountants, people prepared to work right here in Troncones so that the inhabitants and visitors of Troncones do not have to go elsewhere for their administrative and health needs, all the other things they need to resolve their lives. Right now, those who are continuing with their studies to a professional level can be counted on the fingers of one hand. We need that to change, but I understand why it’s so hard to leave.

Troncones has an energy that’s unique. You hardly find a more beautiful place than this one. Today, I work elsewhere, but I taught here from 1998 to 2023, then I left for a year to Zihuatanejo as an administrator, and came back to teach in 2024. This school year, my service has me away in the mountains but I want to return to Troncones. Why? Because I want to go to the sea, I want to go to the forest, I want to fish, I want to enjoy the beach with my family, to swim, to live together, to feel alive with the coexistence of nature. I completely understand, for the inhabitants here, that once they are employed here, why it is so difficult for them to leave Troncones. Today is Sunday. There are so many options in this town for people to have fun. It’s not like other boring places, is it? This place has life. So, it’s no wonder that people who come here, once they get to know it, no longer want to leave Troncones. That’s why it’s growing a lot

Today, there are many more of us in Troncones. Hopefully, Troncones’ natural resources remain sufficient to supply the entire population. Even when I arrived here in 1998, Troncones already had the problem that it does not have enough water. The water that reaches all the houses, all the businesses, is water that comes from subterranean reservoirs, reservoirs managed by the ejido. In this part of Troncones where we are here, at the school and the church, water only arrives on Mondays and Tuesdays. Families have to get ready to fill their pilas [wash basins] and their water tanks in those two days so that they have enough water for the whole week. Because of this problem with the water, the ejidatarios have made agreements with neighboring ejidos, ones that have rivers, such as the ejido of Lagunillas. Troncones does not have a river. Those neighboring ejidos have been sending water here to supply specific areas of Troncones, like along Manzanillo Bay on the north end of Troncones. Hopefully, in the future, the government will invest in these types of sustainable projects so that there is enough water in Troncones, so that the homes, the families, have this vital liquid for food and hygiene.

So that’s what I observed when I arrived and what I observe now. The beauty and the community, what’s been happening. And what’s needed now: more water and more access to education. The vertical growth, the professional part, is a little difficult to achieve in Troncones because the foreign community resolves the life of its inhabitants, through work in their houses. In the places where the government has sent me to work, I see many professionals there, teachers, accountants, engineers and architects. The need for growth meets the possibility of making a living there. But here in Troncones, the need is met by the foreign community. That is a reality. I hope the foreign community keeps producing work for the inhabitants and neighbors of Troncones, but it is also important that the inhabitants grow professionally because, if they have a profession, they have the possibility to be employed by the foreign community or to be employed outside of Troncones. That is something very important that we should all consider.

LOT: What drew you to education? What motivated you to become a teacher?

Santos: I come from a family of very low economic resources, economically poor. My mother was a homemaker and my father was a fisherman. There was always a need. At home, we ate a lot of fish. But sometimes the work of a fisherman does not always bring money home, because sometimes you catch fish and sometimes you don’t catch anything. When you don’t catch anything, you don’t eat, there is no food, but you still have to pay the electricity, you still have to pay the gas, you still have to pay school fees, you still have to pay the expenses of a household. I wanted to live differently so I worked hard in school. I worked hard to be among the best students, to see if I could earn a scholarship. I had the effort and the will. That gave me the possibility of earning a scholarship so that I could study. When I got out of telesecundaria, I went to high school at the Centro de Estudios Tecnológicos del Mar #16 (CETMAR) in Lázaro Cárdenas. There they gave me an academic scholarship for my average, they gave me a food scholarship and they gave me a transportation scholarship. The three scholarships were given to me because CETMAR does a socioeconomic study of its applicants, determining what condition they are in financially, mentally and intellectually. At least, in 1994 and 1997, that’s what they did with my group, that’s how it happened for me.

When I finished at that academic level, when I finished CETMAR, I had a problem, because where I lived in Petacalco, there were no more schools for me. I had to go to Morelia or Acapulco or Chilpancingo to be able to study, but to go to those places I had to rent a place to live, I had to buy food and I had to pay tuition. For one year I stopped studying, because my parents told me that there was no more money for me to study. My scholarships had ended. When I finished CETMAR, there was no more possibility. Since my father was a fisherman, I went to fish with him. It is a very nice job. In fact, fishing is an exciting and beautiful sport. But it is also dangerous. It is a marvel when you get a boat out into the depths, out in the open ocean, and you’re there with the movement, the swaying of the waves.

There you stay and fish, waiting. Waiting for a fish to come and bite the hook on your line so you can catch it. There’s no guarantee you will do well, because sometimes the fish want to eat, sometimes they don’t; sometimes they’re here and sometimes they’re not here. I spent a year like that, fishing. I learned. I developed fishing skills, and from living with the sea, I saw how insignificant and small I am before the world and what I am: a little living thing and that at any moment nature can take your life away from you. In that year I was fishing, there were times when suddenly there were big waves, rainstorms where you couldn’t look to see how you might get out. Fortunately, we had a good captain who always, when bad times came, always got us out of it, even when there was water coming in over the side. The fisherman’s life is beautiful, but it is also very dangerous. I still remember my father saying, “The sea can make you rich overnight, but the sea can also take your life overnight.”

Nature can be so generous that you get lots of fish. But sometimes you get nothing. I want to make a confession. It made me despair. It discouraged me to some extent. There came a day when I climbed along some rocks by the sea, until I reached an edge. There was nowhere else for me to climb. The waves were crashing. I was up there alone. At that moment, I wanted and tried to make a connection with the great architect of the universe, with God. I remember looking at the sea, the boats passing by and saying, “God, is this everything for me? Is this all there is to it? What good did it do me to work so hard in school? What will become of my life? I have a family to raise. How am I going to support my family if I don’t have a well-defined job, a job with certainty?” And then I said, “God, help me.” I prayed from the bottom of my heart and mind that opportunities would come for me to continue studying. It may be hard for some human beings to understand what happened next for me. Today, in my role as a doctor in education, it is assumed the more you study the more you detach yourself from certain beliefs, that you should be more scientific.

But life teaches you some deep, strong lessons. There exists something, or at least there exists an energy. Call it what you want. For me, it’s “God.” In other words, I asked God and it came to pass. 20 days after I tried to communicate with the energy of the universe, a teacher training project called Guerrero 2000 arrived in the municipality of La Union. That’s a project that magically came to resolve my life. I was coming in from fishing one morning and there was a man with a fishing line on the shore, humming. He was a teacher–Professor Enrique–who worked in Petacalco, in a place called Guárico. He was called out to my father, “Tiburon, Tiburon, my father’s nickname [Shark], why don’t you take your son to La Unión? For him to study to be a teacher? Take him.” At that moment, we were sleepless, but we arrived at the house, we cleaned up, I grabbed my documents and we went to La Unión. We arrived and I met la maestra [teacher] Martha Eugenia Serrano Limón, who came from Mexico City to promote the project, which they called Modelo de Formación de Docentes, Guerrero 2000 [Teacher Training Model, Guerrero 2000]. Only the best students, with the best averages, from the municipality of La Unión and Coahuayutla could enter this project. I brought a very good average from CETMAR.

Martha Eugenia Serrano Limón was the first cousin of the Secretary of Education, Miguel Limón Rojas. She had a very strong character; she was a serious person. She took my documents, looked at them, looked at my average. Then, Maestra Martha looked at me, and said, “You have a very good average, but you’ve already lost a year. Only 50 students will be admitted. Leave me your documents. I can’t guarantee you will make it, but if we don’t complete the 50, you’ll come in. But if all 50 are filled, you won’t be in.” Híjole. Wow, maybe I’m in, maybe I’m not in. I felt a little sad and I didn’t know what to think. The next day we came back, and Maestra Martha told me, “Congratulations. You’re in. Welcome.” And I entered the Guerrero 2000 program in 1998.

The program consisted of studying in the municipality of La Unión, on Fridays from 4 to 8 p.m., Saturdays from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., and Sundays from 8 a.m. to 12 noon. From Monday to Friday during the day, you had to work as a teacher. It was a nice project because you worked with the children in the schools during the week and on Friday you would return to La Unión, to the teacher training, to study, to prepare for the next week. What I learned in the program, I applied in the community–the knowledge, the strategies, the methods, the issues related to dance, to the arts–everything Guerrero 2000 taught me, I applied it fresh.

The people of the community of Troncones liked this approach and supported me. I did what I was supposed to do as a teacher during the week, but then went to learn more on weekends, to do my share to help the community to get out of an educational backwardness. I did as much as I could to find a way for the children to be happy, to enjoy the knowledge of everything they learned. I tried to encourage enjoyment. I tried to strengthen harmonious relationships among them; to teach them about practicing a healthy life, in sports, in knowledge; to develop in them a comprehensive education. The Guerreo 2000 teachers told us we had to develop an integrated education, that we had to attend to three spheres in the students: first, the cognitive part, everything that has to do with knowledge. The second, the socio-affective part, which has to do with human relations, values, being polite, coexistence, all that. Third, was is the psychomotor part, the developing a connection between the mind and body, in sports, to get our students to move, to do physical activity so that they can have a healthy life.

It became clear to me through the Guerrero 2000 program that I was not becoming a teacher to transmit knowledge, instead, that I had a responsibility to develop children’s skills in human relations and physical activity, not only knowledge, that I had to make sure I was offering an integrated education. There was an agreement between the Guerrero 2000 program and the educational authorities at the Ministry of Public Education in Chilpancingo, that once we finished the program the Secretary of Public Education was going to assign us to the place where we were as students, the place we had been making connections and progress, that once we graduated as graduates in primary education that we would stay in our communities. But then the national teachers’ union interfered in that plan, saying, “You can’t stay there. You’ve done your work. You need to go somewhere else, to the mountains. If you stay, you’re interfering with the rights of other teachers to teach where you are.”

The authorities of the Guerrero 2000 program questioned that, pointing out, in my case, that the union hadn’t covered Troncones previously. The education authorities of this area intervened and so did the parents of Troncones. They, the parents, were happy and eager for me to stay here working in Troncones. A delegation from Tecpan [a municipality in Guerrero] came here to the Costa Brava restaurant to resolve the situation. I still remember what the delegate said, “Many times we are summoned to different places to solve the problem of teachers that the towns do not want, and this is an incredible thing because we are here to solve a situation of a teacher that the town does want.” The delegation, due to the requests of the parents, decided that I should stay here and work. That was very good for me. I was able to continue my teaching work at the primary school with the purpose of implementing what I had learned in the Guerrero 2000 program. Besides, going back to the first question, Troncones is a wonderful place. What happened with me, and what happens with other people who come to visit, is that once you get to Troncones, you don’t want to leave Troncones.

In Part Two, Santos describes the strengths and weaknesses of the Mexican educational system, the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in Mexico and the defining characteristics of Mexican culture. There’s also some recent personal news you’ll want to celebrate. Come back. Meet Santos, again.

%2017.27.38.avif)

.png)

.avif)