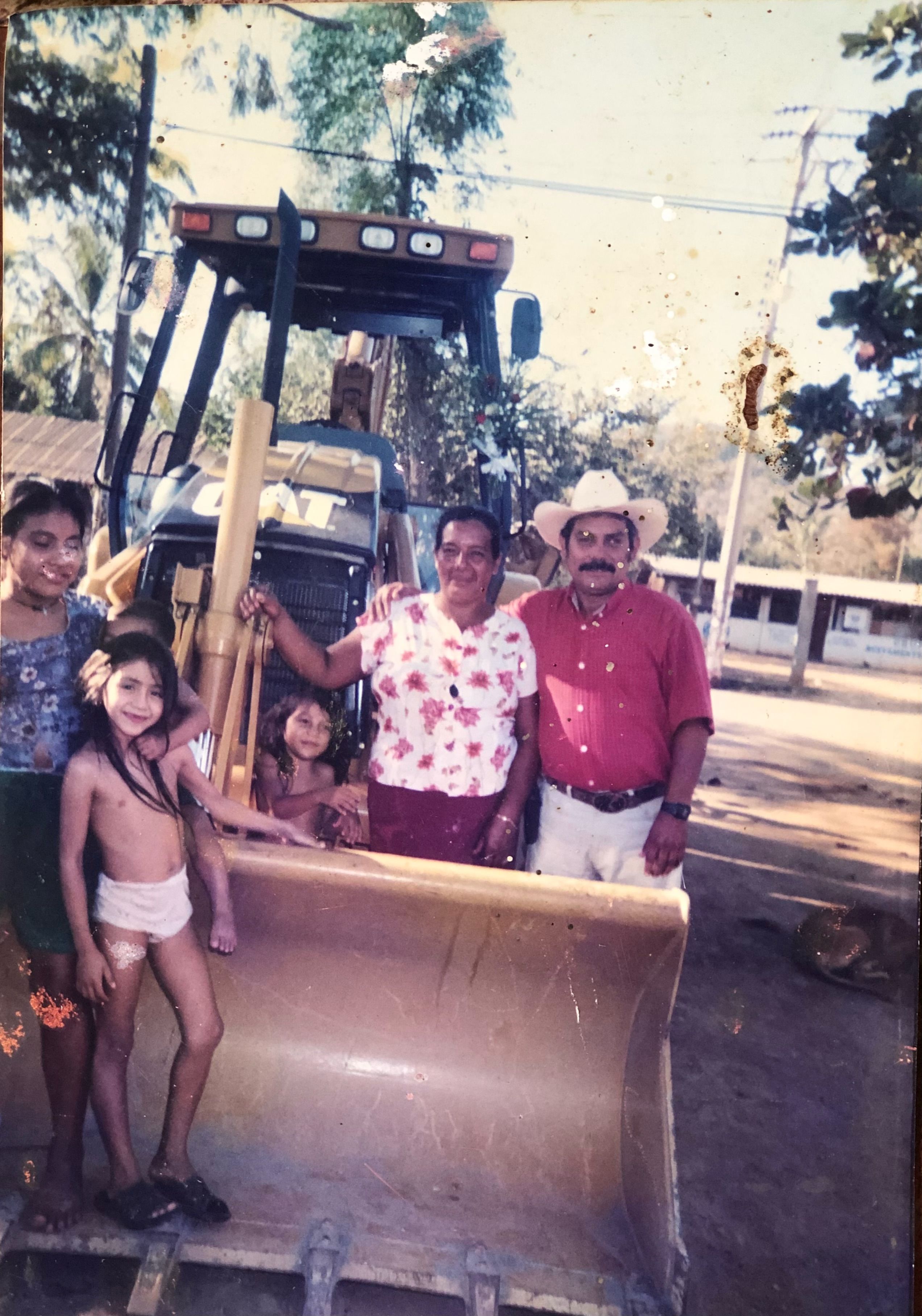

Doña Matilde: It Wasn’t Easy

The move to Troncones required a lot of patience and work—there was nothing here

Life was hard for the families who were re-settled here in 1976 by the governor of Guerrero. No houses. No water. No work. Somehow, they made it through and created a village that’s known for its determination and tranquility. Enedino Sanchez told me Doña Matilde knew the stories of how that came to pass. I went to see her. Members of her family were there when I interviewed her. I was nervous about having them listen. I was glad when they joined in.

LOT: What is your full name?

Doña Matilde: Matilde Lujano Alfaro.

LOT: Where do those names come from?

Doña Matilde: Those come from the mountains above San Luis de la Loma, from the municipality of Tecpan [south of Zihuatanejo, between Petatlán and Acapulco]. We came here from Infiernillo, near La Saltitera.

LOT: How old were you when you arrived here?

Doña Matilde: A little over 20. I was already married, with two children.

LOT: What are your first memories of Troncones?

Doña Matilde: Living under the trees. We didn’t have a house. Our beds were woven out of rope and wood. The mattress was petate [made from dried palms].

LOT: Did you like living like that?

Doña Matilde: At that time, it was normal.

LOT: How did the families decide where to build their houses?

Doña Matilde: Since it was communal land, we were given plots and we built dirt houses—houses framed out of sticks, and filled with stone and coconut husks, then covered in mud. That kind of house is called bonote. Those were the first houses that were built. Later on, we made the first brick house in town, using concrete bricks.

LOT: How many families were already here, in Troncones, before the people from Infiernillo arrived?

Doña Matilde: There were some Spaniards. Maybe five families. Maybe less. It wasn’t a lot. Maybe 20 people. We called them “colones” [colonists]. They were caretakers, looking after the land for people who lived in Mexico City.

LOT: How many people came from Infiernillo?

Doña Matilde: We arrived—me, my husband and our two children—with my mother-in-law and three brothers, who already had families. I don’t know exactly how many we were in total, all together. We were about 40 families, maybe a few more.

LOT: What was Infiernillo like? The name translates as “Little Hell”.

Doña Matilde: It was almost the same as here. It was a place where we grew crops, had pastures for animals. But it wasn’t communal land. There was no ejido. The land had owners and we were kicked out. We were moved here. The governor of Guerrero, Rubén Figueroa, decided that. In those days, he was the law.

LOT: How did you arrive here?

Doña Matilde: In a volteo, in a dump truck. Like we were cows. With our children. The men made several trips. They brought whatever we had.

LOT: Was anything prepared?

Doña Matilde: Some men came about three times and made little clearings and set up some palapas, but those were knocked down each time they came back. Figueroa had to come tell the colones not to do that anymore because, if they didn’t leave our things, they were going to have problems with him. If Figueroa told you, “Do this,” you were going to do it, because if you didn’t, well, the next day you’d be gone and you’d never be found.

LOT: What did you do for water? For washing and drinking?

Doña Matilde: There was a well over there [pointing towards the mountain]. We used to wash there and made little wells to collect drinking water. It’s all dried up now. Later on, we had to make deeper wells. We used to line up at those little wells to get water to drink. And to go wash, too. Only about four people could wash there at a time, grabbing the water with buckets, putting it in drums, in tubs [tabos and tinas]. Sometimes, the women fought to use the water. The ones who got up early brought their clothes and put them there wherever they could. Then, others would arrive and sometimes they would go at it. They would grab each other.

LOT: How did the people from Infiernillo get comfortable and stay cool?

Doña Matilde: There were a lot of fig trees then. Big ones. They created a lot of shade. It rained a lot more in those days. Those trees dried up as the water dried up. When we first arrived, it wasn’t easy. Me, I wanted to go somewhere else. I didn’t like anything here. There was nothing to like. Nothing at all. The water for washing—and the well for drinking—was a very, very sad thing. Several children got sick from the water. There were a lot of minerals in it. We would boil that water for coffee and it would leave a white layer at the bottom of the pot. Some children died. We think it was from the water. But we all got used to being here. Gradually. And now, I don’t want to go anywhere else.

LOT: What would the people who came to Troncones in 1976 say about Troncones today?

Doña Matilde: That now, it’s much better. Because when we arrived, it was dismal. There was no church. There was no school for the children. There was nothing. Not even work. Everyone had to go out to work in other places, stay there the whole week and then come back here on weekends. They would bring money home. There was no money here back then. Many people worked in the hotels in Ixtapa. Other people went to Zihua and Lázaro, wherever they could find work near the highway. No one had cars. Everyone had to walk to the highway. There were women who sold tamales in Zihua. They would leave here around 3 or 4 in the morning, walking all the way to the highway and then finding their way to town. There were farms to the north of the village back then. That’s where they grew their corn.

LOT: What makes you happiest about Troncones?

Doña Matilde: That we aren’t uncomfortable here anymore. That we have schools for our children. That it’s not like before. That we don’t have to rely on catching little animals [animalitos] from the ocean to have something to eat, to keep ourselves alive.

LOT: What is Troncones missing?

Doña Matilde: A park. We need a park for the children to go to and for the older people. That land over there would be a good park [pointing to the empty lot next to her house, where there’s a large parota tree, on Main Street]. I don’t know who the owner is right now, but I don’t think whoever it is will want to donate it for free. About 20 years ago, we started to clear land for a park behind the church, but nothing came of it. Now that lot is covered in monte [wild brush and weeds] and we still don’t have a park.

LOT: What was something you looked forward to when you were raising your kids?

Doña Matilde: Through the church, we would gather on Manzanillo Bay almost every Saturday afternoon. It was a retreat organized by the church, but it was mostly social. It seemed like almost everyone in town would go. Back then, Manzanillo wasn’t inhabited. We’d go there in Ventura’s oxcarts. He had some oxen, big like bulls, and he had a cart. Sometimes, we’d go to other places, but it was mostly to Manzanillo Bay. There were times when priests would come from the outside, from La Unión, to join us, to talk about prayer. But what they really did was join us in playing games and having fun.

LOT: Enedino says you have many stories and, if someone doesn’t write them down, they’ll be lost in the wind. What are your favorites?

At that point Doña Matilde got quiet. Her son-in-law, Jorge Luis Rosas, who’s proudly and better known as El Gordo, tried prompting her, suggesting stories that caused her to shake her head. A lot of them seemed to be gossip, chisme, stories that cast one person or another in an unfavorable light. Doña Matilde didn’t want to gossip. Finally, El Gordo broke the ice.

El Gordo: Tell him about the day the ocean was going to surge and flood us.

Doña Matilde: When the ocean was going to surge? [In Spanish: ¿Cuando vas a salir el mar? Literally, when the ocean was going to leave.]

El Gordo: He wants to know our history. That story says a lot about chisme in Troncones.

Doña Matilde: That everyone left here because they were scared?

El Gordo: This is something that happened about 12 years ago. A rumor started. Some men from the Navy came here and said to be careful, that the ocean was going to surge, salirse. The story became that the tide was going to wipe out the town, that the ocean was going to rise up and flood everything. Everyone who was here grabbed their kids and started walking up the hill, towards the highway. It was a misunderstanding. That wasn’t what was said. The warning was that the tide was going rise [subir], not that the ocean was to leave [salir]. People were running with their things. People went to other towns.

With everyone laughing, her daughter Marvella chimed in.

Marvella: I grabbed my kids and we left in a taxi. It turned out fun for the people who left. We had a nice get-together, with coffee and bonfires, there at the entrance, where there was an abandoned restaurant.

Doña Matilde: Many people didn’t leave. We were waiting. We decided we’d go if we heard or saw anything, that that’s when we’d run. It turns out it was just gossip. Crazy-making gossip.

LOT: What’s important about Troncones? Why do people come here now?

Doña Matilde: Because they like the beach. They come because it’s a quiet paradise, because it’s peaceful, because everyone is treated the same and looks out for each other. After being here about 10 years, things started to get better. We had fields planted with corn, pumpkins and beans. There was plenty for us to eat. After another 10 years, the foreigners [extranjeros] started to come and there was more work. We fit together really well with the foreigners. That’s helped Troncones grow economically over the last 20 years or so. And now with the foreigners’ support, through Las Hermanas, our children have more opportunities. That’s an enormous change from when people took pity on us, when they said we didn’t have anything.

%2017.27.38.avif)

.png)

.avif)