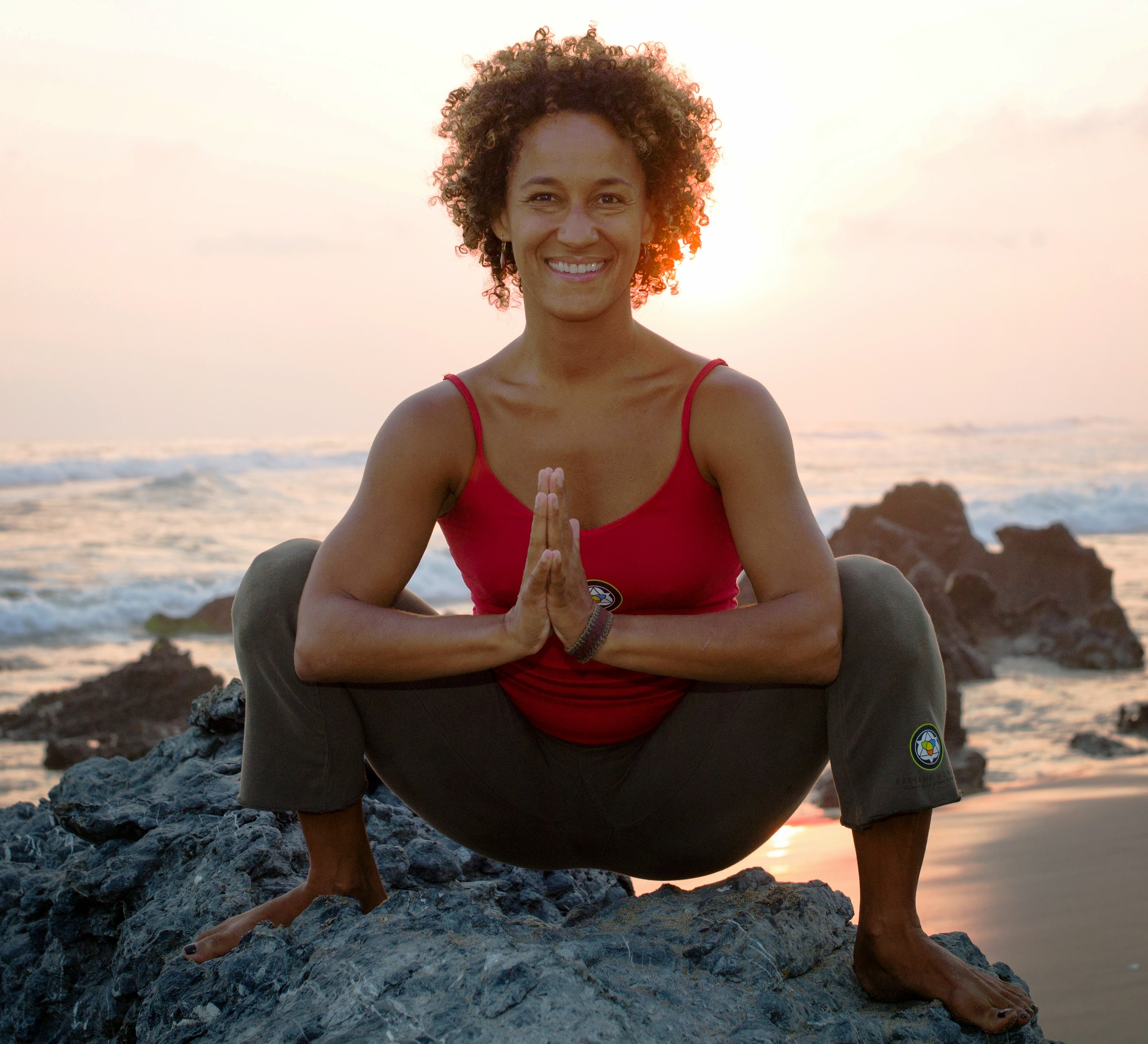

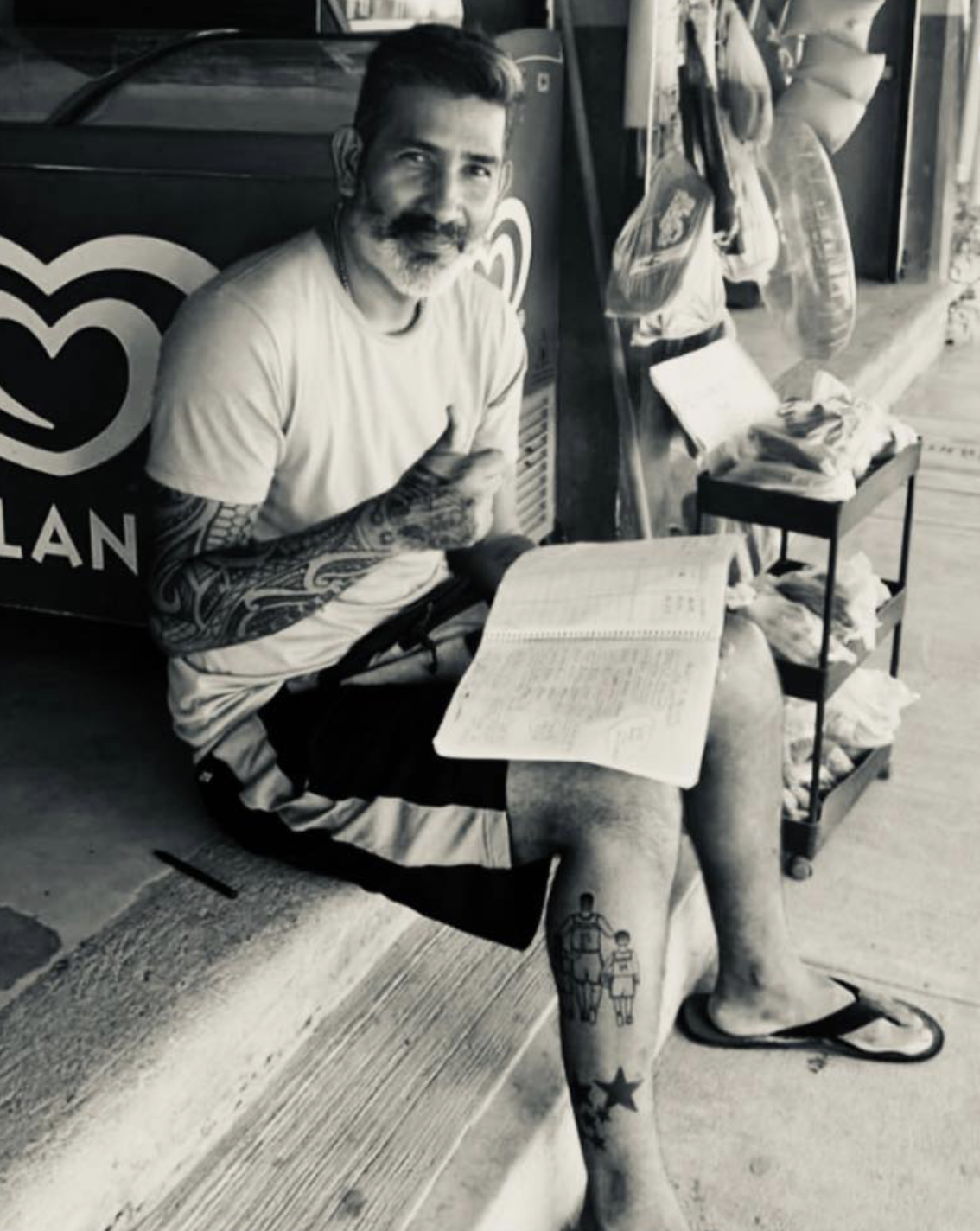

Jesús Santana Morales: Coach Chucho

A talented Troncones-born athlete passes on lessons to the next generation

“How you play the game is how you do everything” is something coaches say. Whether that’s true or not clearly depends more on the individual than on the task at hand. What is true is that coaching kids is a privilege. Good coaches understand that—that coaching is an opportunity to teach kids how to be good teammates, how to prepare each other to get through difficult situations and how to make sure no one feels left behind. Coach Chucho is a good coach.

.jpeg)

LOT: How did you start playing basketball and working with kids?

Jesús: The first basketball court in Troncones was built around ‘93, ‘94. I was about 14. Nobody knew how to play basketball. Nobody. Still, we’d all go to the court, grab the ball, and we’d shoot, but we didn’t know how. We’d dribble with two hands and all that. From there, I started learning. I began watching basketball on television. I particularly remember the NBA finals in 1997, the Chicago Bulls against the Utah Jazz, watching Michael Jordan. I started to see myself in him. That’s how I started learning. And from there, I went on to play in Zihuatanejo and La Unión. We were champions twice in the La Unión league, the Troncones team. We started together on that first old court. After it was built, it never got painted, except the sidelines. So, we painted it—me, my cousins and some friends. I learned how to draw the Bulls’ logo, I did it on the backboard and on the floor.

I didn’t jump into coaching, into giving classes, until these two new courts were built in 2022. I did it for free, because it came from my heart to do it. Right away, like a month after I started training them, we went to Zihuatanejo to compete in the league. From there we went to Morelia to compete, then to the State of Mexico. We were in tournaments and things went very well for us, until my truck broke down. I’d been taking the kids to those tournaments in my truck and I couldn’t do that anymore. As much as the parents tried, we couldn’t keep it going. Once I got a new truck, the interest wasn’t there as much—the next set of parents couldn’t go watch the games as easily and the next set of kids liked volleyball more than basketball. So now, I’ve taken up coaching volleyball. We’re getting there, getting ready to compete. I’m not saying we won’t go back to basketball one day.

LOT: It’s volleyball over basketball now?

Jesús: Yes, right now, it’s working out better for them. When you go out and play elsewhere, there are a lot of expenses—for referees, for water, for travel, for places to stay. Here, right now, they’re in town, they’re at home and that’s it. We pay for refereeing and water, and we don’t have to leave anymore. We’re not leaving and coming back late. There were times I came back with the kids 11 at night. Their parents would be calling me, “Hey, how are they?”, “Where are you”, “What happened?”. It’s a lot of responsibility to go out of town with them.

LOT: Have you ever done classes for adults? For people over 60?

Jesús: One time, I had like six or seven adults, 16 years old and up. But no one over 60, yet. The oldest volleyball player has been a woman, who was about 50 years old.

LOT: What sports did you play when you were little?

Jesús: When we were in school, at about the age of eight, we started playing fútbol [soccer]. And baseball, but we called it, “Let’s play batting”. That’s what it was, batting. We did that on the beach.

LOT: Of all those sports—baseball, fútbol and basketball—which one did you like best?

Jesús: My favorite is basketball. Not because I managed to stand out a little bit. And not because I’m one of the tallest. It’s my favorite because it challenged me. We used to play pickup games, one-on-one and 21, against the teachers. There was a teacher who was very good. His name was Cande Candelario. One of my biggest challenges was beating him at 21. I couldn’t beat him. I just couldn’t beat him. About three months later, I could finally beat him, and then he couldn’t beat me anymore.

Basketball is a sport that has everything. All the movements—you jump, you crouch, you spin. It’s a fast-paced sport, one of the fastest. Aside from that, you meet a lot of people. Through basketball, I have many friends, from many places. I’m beginning to like volleyball more now, especially when it’s played clean, with fingertips and bumps. It’s not always played that way here. Sometimes, we play a “dirty volleyball” [voleibol cochino]. That’s when you’re allowed to grab the ball, catch it and throw it, like they do basketball. I like the bump-set-spike game better.

LOT: What do sports teach you?

Jesús: Each one has taught me to play fair, be honest, be kind and pay attention. In basketball, I’ve always been considered someone who plays clean, someone who knows the game. I don't go around hitting people, and when I do hit someone by mistake, I say later, “Excuse me, it wasn’t my intention to hit you.” Playing sports has taught me a lot about honesty and loyalty. On the court, I have no reason to hit a player when someone could do the same to me. We are friends on the court, even when we are opponents. And if we’re friends outside, there is no reason to become malicious inside.

LOT: What age children do you coach?

Jesús: I first started with the kids from six-year-olds up to 16-year-olds. And I’ve stayed with those ages. They’re eager to learn. I try to instill in them a respect for their teammates, that when we arrive at the court they can’t be pushing each other around or saying bad words. I try to teach them how to be polite on and off the court, so they won’t be going around causing trouble for themselves later. We have a rule that the oldest looks after the youngest. The kids pick up on that; they do it. I also try to get them to understand, on the court, that there’s no yelling at each other, no complaining at each other—I want them to understand the idea of camaraderie, that they’re teammates, that there’s no reason to yell, even when things are difficult and even when there are kids who are mad.

LOT: What do the kids teach you?

Jesús: I’ve spent almost four years with the kids now, practicing, teaching them. I’ve learned a lot from them. Each one has their own qualities. I’ve laughed with them, cried with them—it’s another sort of camaraderie. I like it when they see me on the street and yell “Coach!” or “Chuy” [Chuy is a common nickname for Jesús]. They teach me respect, honesty, kindness and compassion, in new ways, every day. They make me a better coach.

LOT: Do you still work with the kids?

Jesús: Right now, we’re on a break. Yes, I’m going to go back. God willing. I just need to have a talk with the parents. About details, like schedules, uniforms, those things. Being a parent is complicated now. That’s one of the reasons I started coaching. It let me do something I enjoy and it also helped me get kids playing together. I saw it in my kids—they’re 18 and 9 now—I was watching them on their phones. One, two, three, even four or five hours, looking at their screens. On the court, there’s none of that. Three hours, no cell phones, no electronics. No digital life. No getting into the bad life.

LOT: You have the build of a younger person. What do you do to keep yourself fit?

Jesús: I walk a lot, especially in the afternoon. I have a motorcycle, but there are times I don’t use it. From town to where I live, it’s 800 meters. I walk it. There are times when I work from Monday to Friday, and on Saturday and Sunday I go out running—sometimes on the road, sometimes on the mountain—jogging. And I play volleyball. It helps that I don’t drink or smoke either. I never have. Well, once. In ’99, some kids I was with, who were from Zihua, rolled a marijuana joint and I tried it. I wanted to go surfing that day but I couldn’t because I got very sleepy. Very, very sleepy. I didn’t like that. I like to keep myself physically fit.

LOT: How did you come to own a pastry shop, la Pastelería Maddy?

Jesús: Oh, that’s my wife, Vanessa. I help here and there. Vanessa’s a very good cook. On a trip, she became interested in baking and she started watching videos to learn. The first cakes she made were for us, for the family. From there she said, “I’m going to start selling cakes.” And she did. Then, people started asking for them. “Can you make a cake for my daughter’s birthday?” And she would do it. That’s how she started and she kept perfecting them. Then, she said, “I’m going to buy myself a large mixer.” Then, it was “I’m going to get a display case.” Vanessa put a large display case in her mother’s store [Super de Maria] and soon she had more orders. Now, she has her store. When the fair comes around in February, we set up a cake stand there. I love her cakes, especially the cheesecake. It’s one of the reasons I go out and exercise. I like eating her cheesecake.

LOT: What was Troncones like when you were little?

Jesús: Very, very beautiful. There were hardly any houses in town, and only three houses on the beach–one in Manzanillo we called “La Casa de Piedras” [The Stone House], another we called “La Casa de Toro” [The Bull House, now known as Casa Blanca]. That house really didn’t have a name back then, but we called the husband “El Toro” and the wife “La Torá” [Mrs. Bull]. And there was Casa de la Tortuga. That was it; those three houses. Until about ’92 or ‘93. We spent a lot of our time back then looking for iguanas, catching them. We’d eat them. Some people would want to buy the iguanas we caught, so we earned a little money. There were so many iguanas then. We’d get them as they went to lay their eggs. Iguanas with eggs were worth more.

There were no cement houses in Troncones at that time. Only houses made of sticks, mud, and split coconuts—bonote, we call it. The sticks held the coconuts, and the mud covered and held everything together. When it rained, some of the mud would wash off, but it didn’t cause any problems. Those houses were very beautiful, and they were cool inside. They had cardboard roofs, a black cardboard I don’t think they even sell anymore. At Christmas and New Year’s, it seemed like the whole town spent those weeks at my uncle Tomás’s house. That’s where the party was. Dancing, everything. It was a good place to be a kid.

LOT: How has Troncones changed?

Jesús: It’s changed, for both good and bad. It’s like a double-edged sword. There’s more work, but things are a lot more complicated. It’s good that we’ve grown as we have—slowly, moderately. Not like a city. It’s also good that nothing has been built over three floors tall, that there are no huge hotels. That’s helped us protect our natural environment—the animals, the trees, the rivers, the lagoons, the beach—our quality of life.

.jpeg)

LOT: How do you see the Mexican community and the foreign community mix? Have you had kids from the foreign community join your practices?

Jesús: I’ve only had one Canadian come join us. He came for two years. No one else has come very long. Maybe that will change in the future. The majority of young boys all over the world like basketball. Keeping them together would be easy, even if they don’t speak each other’s language. We once had two girls, who were about 14 years old, and a boy, who was 15, come to play basketball. In the game, everything was fine. Everyone knew the same movements.

LOT: What do you like most about living here?

Jesús: I like the tranquility. Everyone is very kind and our town is very beautiful. We have everything here: sea, beach, forest, jungle. In the rainy season, we have a creek that looks like a river and it makes pools for swimming. I’m a motorcyclist and I’ve traveled throughout Mexico, to Michoacán, Chiapas, Veracruz, Mazatlán, Veracruz, the State of Mexico, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí. To many places. Towns like Troncones are very few. Our tranquility, our natural resources, our safety. It is very safe here even though throughout almost all of Mexico, the country, things can feel very unsafe. You can see and feel the peace here. That’s what I like. I was born here, and truly, like the song says, “aquí nací y aquí moriré” [here I was born and here I will die].

LOT: Okay, your tattoos. I know they all have stories. How’d you start?

Jesús: I surfed from about ’97, from when I was about 17, until the shark attack in 2008. I surfed Manzanillo Bay a lot, almost daily. My mother-in-law [Maria Solis] had a restaurant there. I got to know an American there, a Hawaiian, whose name was Kevin. He had a tattoo that wrapped his arm and I asked him about it. He told me it was Māori [a pattern of the indigenous people of New Zealand], and I thought, “One day I’m going to get a tattoo like that.” That’s how I started. Then, later, I got more. Then, more and more. I have one for volleyball because I like volleyball. And since I’m a motorcyclist, I have all the motorcycle brands I’ve owned. I have my daughter’s name. My son’s, my wife’s. My mom. My dad. It’s like an addiction; you get one and then you don’t want to stop.

LOT: What do you want to see become part of the culture here?

Jesús: I’d like to see us have a cultural center, a place to express who we are, a place to display our local history, our traditions, so the people of the future, our children, our grandchildren, can know about our roots, about who participated in making this such a beautiful town. That would be interesting for tourists, too, I think. A Troncones Cultural Center, like a museum, so people can know a little more about what the town was before and how it has formed. When people arrive here, I can tell that they feel like they’ve found another world. I’d like to see us celebrate that.

I sent this article to Jesús to make sure I had the facts correct. He sent me back this note. I thought it made a good post-script, a follow-up. I especially liked how he closed. Translated from his WhatsApp message.

My name is Jesús Santana Morales. I am a native and original resident of Playa Troncones, a place where there was no basketball court until around the year 1993 or 1994, when the first court was built. At that time, it was like a fever because everyone went to play every afternoon and night. That was when I began to fall in love with this beautiful sport called basketball. In that period, the Sunday basketball league opened in the municipality of La Unión, where all the teams traveled to different small towns to play all day under the sun. The towns included Zacatula, Naranjito, Petacalco, Coyuquilla, Sorcua, La Unión, Los Llanos, Lagunillas, Ciénega, Troncones, and many more. The Troncones team became champions for two consecutive seasons. Later, around 1996, I began playing in the Zihuatanejo league with the Pantla team, and little by little I continued playing in many teams in the Zihuatanejo league. I became the only basketball and volleyball player who remained active in these beautiful sports, and that is what pushed me to begin training the children of my town, Troncones.

For many reasons—one was so that there would be basketball and volleyball players here, because soccer is what dominates here (and I’m not saying that’s bad) but I wanted basketball and volleyball players in my town too—another reason is the way life is now with technology, children are always behind a cellphone, iPad, tablet, video games, TV, and many other things. So it was on Monday, July 11, 2020, that I began with this wonderful dream and project: the JSM Basketball and Volleyball School of Playa Troncones. Nobody believed in this project, and there were many obstacles, but I have shown that when you truly want something, it can be done.

With this small dream made reality, we have already participated in state and municipal volleyball competitions in Zihuatanejo and the state of Guerrero. With my own resources, I have taken the children to play in the state of Michoacán (Morelia, Lázaro Cárdenas), in the State of Mexico (El Oro), and in the city of Iguala, Guerrero. Everyone is happy and proud of the children’s participation, which motivates me to continue and continue with this work. I want to emphasize how grateful I am for the parents of my children, who always support us. My dream is to keep going with this project. The goal, as I always tell the children, is to learn how to compete. Competition teaches a lot—whether you win or lose, it teaches you about teamwork inside and outside the court, so that in the future they will know how to be good people in a world that truly needs it. J.S.M.

.jpeg)

%2017.27.38.avif)

.png)

.avif)